Today is one-ten-twenty, a good day to announce a new top-level directory. The past 6 months have been “spent” building:

Collapsologie Immersion

late to the game and eager to learn

Can we seed future successor-cultures in time?

https://ratical.org/collapsologie/

Collapsologie is the study and elaboration of how industrial civilization as we know it collapses and if it does, what will replace it. Industrial civilization is the use of machinery powered by electricity or any form of energy to carry out various activities. Collapsologie is a neologism developed by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens, authors of two books: Comment tout peut s’effondrer. Petit manuel de collapsologie à l’usage des générations présentes (2015 – Eng translation coming Spring 2020: How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times) and Une autre fin du monde est possible. Vivre l’effondrement, et pas seulement y survivre (2018 –Another End of the World Is Possible. Live the Collapse, Not Just Survive It).

The end is also the beginning. While only a beginning, Collapsologie Immersion starts to scratch the surface of what we are dealing with, here at the end of empire.

Help! I am seeking persons fluent in French who are likewise interested in this work. From crude google translate at the bottom of Pablo Servigne’s home page:

Collapsology . Here are my two books that have contributed to bringing the issue of collapse to the public square (in a French-speaking environment): How everything can collapse (Seuil, 2015), which deals with findings (collapso- logy); and Another end of the world is possible (Seuil, 2018), which is the opening of the “interior” work site (collapso-logie). It remains to open the “external” site (politics, action, struggles, etc. (collapso-praxis)).

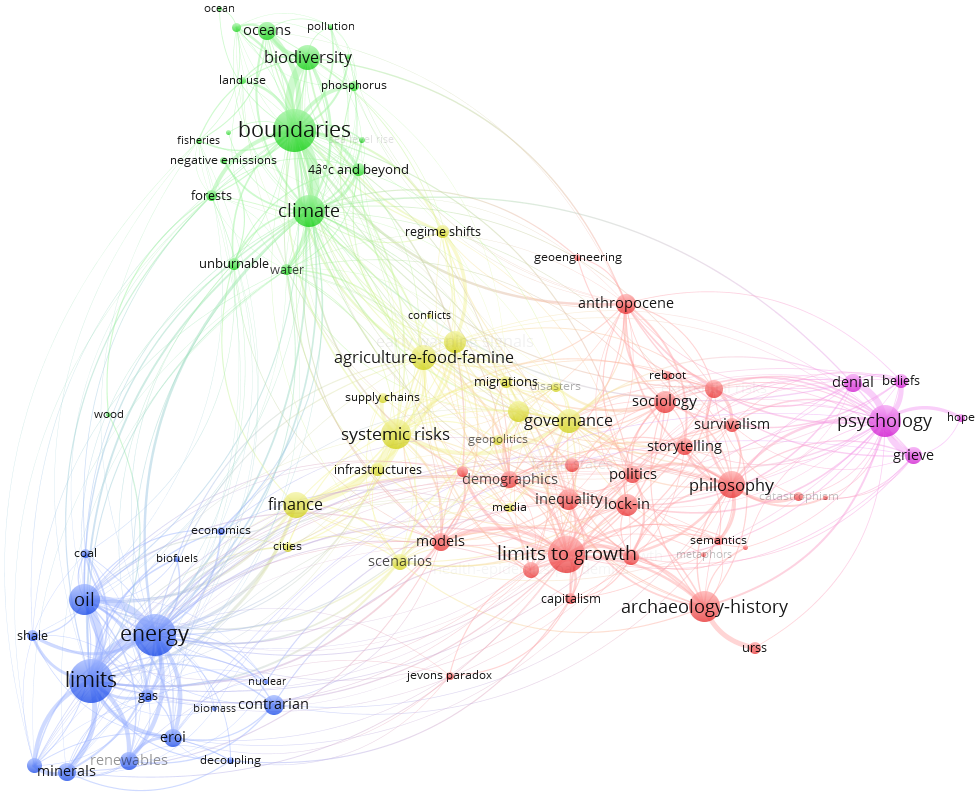

The imperative here is to amplify in English the study, perceptions, and analysis being explored in Europe encompassed within collapsologie. Collapsologie is an applied and transdisciplinary science involving ecology, economics, anthropology, sociology, psychology, biophysics, biogeography, agriculture, demography, politics, geopolitics, archeology, history, futurology, health, law and art. This systemic approach is based on the two cognitive modes of reason and intuition.

“We always said that we have been told and understand that we’re relatives. Where our white brother will talk about water and trees and animals and fish as resources we talk about them as relatives. That’s a whole different perspective. If you think that they’re relatives and you understand that then you’re going to treat them differently.”

One of my many concerns is “Considering Systemic Collapse and Our Profound Dependence on Electricity”:

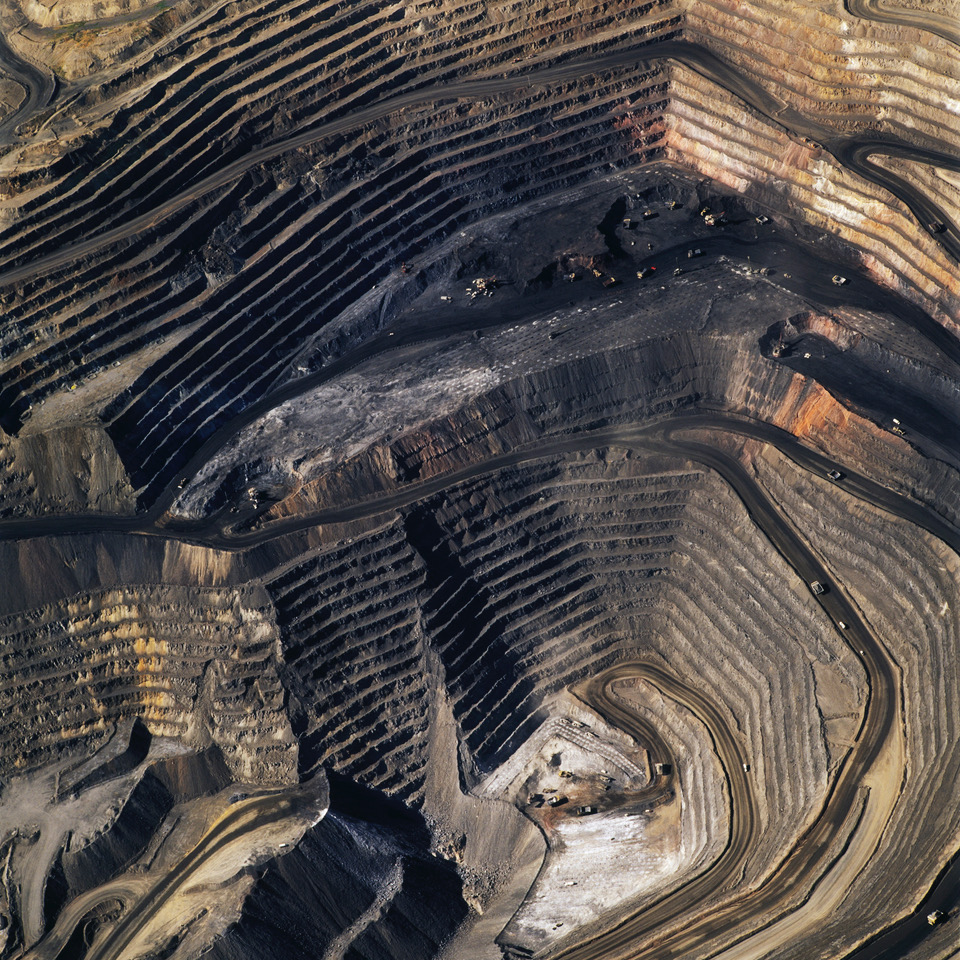

It is becoming ever more difficult to understand how this way of life that depends on unlimited energy can continue. Many writers have written about the impacts of energy overshoot, electrification and Collapsologie. This compilation presents a selection of ones who have influenced my thinking. During the past century, “first world” cultures have become utterly dependent on titanic and continuous supplies of power. For decades, increasing coal, natural gas, uranium and , wood (so-called biomass) -fueled power generation plant operations threatens the health and survival of Mother Earth’s offspring, including humanity.

Given that, as Katie Singer leads off in Limits to Internet Growth, “The Internet is the largest thing that humanity has built”, we are confronted by another serious conundrum. As Singer explains:

Most people now consider Internet access necessary for family connections and educational and economic opportunities. Meanwhile, by 2025, with power-hungry servers storing data from billions of smartphones, tablets and Internet-connected devices, some researchers predict that information-communications-technologies (ICT) could consume 20% of the entire world’s electricity, hampering climate change targets and straining grids.[2] Other analysts claim that ICT could consume 51% of total global electricity and emit as much as 23% of total GHGs by 2030.[3]

Smartphones’ CO2emissions will grow from 4% of total global emissions in 2010 to 11% by 2020. This translates to a jump from 17 to 125 megatons of CO2 equivalent per year—or a 730% growth.[4] Indeed, one smartphone includes more than 1000 different substances, each with its own supply chain.[5]

Given the staggering nature of these statistics, how does any user recognize the true cost of Internet access? Each Google and GPS search; every social media post and video stream; every email, text message and Skype call; every online purchase; every transfer of funds or medical or educational records; every “smart,” “energy-saving” Internet-of-Things-connected refrigerator messaging its owner to buy more milk—every online activity—requires international networks of cell sites and data storage centers that start with extraction of natural resources and consume huge amounts of water and greenhouse gas-emitting electricity. Manufacturing every smartphone, tablet and access network is powered by fossil fuels and workers subject to hazardous conditions. Manufacturing depends on refineries, GHG-emitting power plants, nuclear plants, chemical plants, steel mills, metal smelters, wood (for smelters) and factories of all kinds. Each energy-guzzling, toxic waste and greenhouse gas-emitting operation depends on all of the others. They interconnect by networks of power lines, natural gas pipe lines, cargo ships, trains, trucks, airplanes, shipping lanes, railways, highways, airports, telecom access networks and data storage centers to form one gigantic super factory.

A measure of our dilemma is how much energy is needed and used to continue building the components comprising the Internet (as well as the energy already expended to create what exists today). As Singer writes in Limits to Internet Growth: Embodied energy “is the energy used to mine, refine and transport raw materials (i.e. quartz, charcoal, coltan, cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium); manufacture semiconductors, screens and cases; assemble them for usable products; and ship each item to its end-user. The embodied energy in every device, appliance and vehicle is greater than the energy that it will use in its lifespan.” Another measure of the ecological costs and energy guzzling requirements of 24/7 Internet operations includes the following compilation assembled by Singer.

- The entire Internet traffic from year 2000 equaled one hour of Internet traffic from 2013.

(Mark Mills: The Cloud Begins with Coal: Big Data, Big Networks, Big Infrastructure and Big Power, Sponsored by the American Mining Assoc. and the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity, Aug 2013, p.3)

- The volume of Internet data at least doubles every two years.

(The Exponential Growth of Data, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, 16 Feb 2017)

- Communications Technology could use as much as 51% of global electricity in 2030 and by then its usage could contribute up to 23% of globally released green house gases.

(Anders Andrae & Tomas Edler “On Global Electricity Usage of Communication Technology: Trends to 2030,” Huawei Technologies Sweden AB, 30 Apr 2015)

- A 2016 study from the semiconductor industry reported that by 2040, computers will require more electricity than the entire world can generate.

- Smartphones’ carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will grow from four percent of total global emissions in 2010 to 11 percent by 2020. This translates to a jump from 17 to 125 megatons of CO2 equivalent per year—or a 730 percent growth.

(Belkhir, Lotfi and A. Elmeligi, “Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations,” J. of Cleaner Production, 2018.

- By 2025, with power-hungry servers storing data from billions of smartphones, tablets and Internet-connected devices, the communications industry could consume 20 percent of the entire world’s electricity, hampering climate change targets and straining power grids.

(John Vidal: “‘Tsunami of data’ could consume one fifth of global electricity by 2025,” Climate Home News, 11 Dec 2017)

- Automated processes now comprise one of the Internet’s 4 main guzzlers of energy; they include automatic software updates for apps, video games and operating systems, as well as automatic backups for websites and advertising bots which also operate automatically.

Hazas, M, J. Morley, et al. “Are there limits to growth in data traffic?: On time use, data generation and speed,” LIMITS ’16, ACM, 8 Jun 2016.

In all this it is incumbent upon me to acknowledge that by using this largest machine humanity has ever built to write and broadcast what I think, intuit, and feel is essential to amplify and emphasize, that I, too, am part of the problem of operating this system. I am requiring my share of embodied and electric energy that is using up more of Mother Earth and all our relatives. So far I do not have any “good” answer or response regarding my own culpability in being part of the problem, contributing my share towards energy overshoot and the looming specter of collapse. Part of the study within Collapsologie Immersion is to seek out and identify further threads and processes to list in the What To Do section and to research prospects for seeding future successor-cultures.

Collapse is both an end and a beginning of our future. Jem Bendell has posited: “collapse as inevitable, catastrophe as probable, and extinction as possible [which enables] a shedding of concern for conforming to the status quo, and a new creativity about what to focus on going forward.” Servigne and Stevens advocate neither pessimism nor optimism but rather to be lucid, to see there are other possible scenarios and that our challenge is to adapt our imagination to apprehend these.