This talk gets at something I was deeply affected by in 2015 when making the archive of Dr. Helen Caldicott’s extraordinarily relevant Symposium: The Dynamics of Possible Nuclear Extinction convened at The New York Academy of Medicine. Speaking on Artificial Intelligence and the Risk of Accidental Nuclear War: A Cosmic Perspective, Max Tegmark touched on some of the same aspects Elaine Scarry elaborates a bit more on in the opening portion of this excerpt.

Excerpt from Elaine Scarry 9 May 2019 address at the Nuclear Age Peace Foundations’s 18th Annual Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future.

It’s a special honor to be talking in terms of Humanity’s Future and because that’s the title I thought that I would begin by just mentioning the fact that when I work on nuclear disarmament, I’ve often noticed that one of the groups of people that is most worried about nuclear weapons is composed of astronomers and astrophysicists. When I first noticed this I was kind of surprised by it because, whereas the rest of us are thinking all the time about the Earth I take it that astronomers are often thinking about worlds way beyond the Earth like other galaxies outside the Milky Way.

Thousands of galaxies in galaxy cluster Abell 2744

This one galaxy for example contains several hundred billion stars many of which have planets. So it seemed remarkable that astronomers should care about this little piece of ground in the universe. This next particular photograph, although it’s showing a very tiny piece of the sky—that’s a tiny little fraction of the sky—and yet that photograph contains thousands of galaxies just within one galaxy cluster and each of those galaxies has billions of stars. [Film: Zoom in the Massive Galaxy Cluster Abell 2744 (0:32)]

When I asked Martin Rees, the Royal astronomer of Britain, why he was so concerned about it given that he spent so much of his mental life outside our own terrain he said that if you’re an astronomer looking at that other world you actually care more about the Earth because you realize that what we have here is nowhere else to be found in the universe. That there is no life, certainly no intelligent life, elsewhere in the universe and the miracle of it being back here seems especially precious.

I also asked another astronomer at the Hubble Telescope, Mario Livio, the same question and he gave the same answer: how extraordinary it was to be always having one’s mental life projected out into this world of other universes and to find again and again that there was no other life or certainly intelligent life out there.

Mario Livio went on to explain the fact that several decades ago a famous scientist, Fermi, pointed out that it’s almost incomprehensible, given the number of planets that recreate the conditions necessary for life, it’s almost inexplicable that we haven’t yet encountered other life. This has come to be known in science as Fermi’s Paradox; the fact that there are so many—millions of places that ought to be showing us life and yet we haven’t found it.

Mario Livio said that different explanations are given for this and one is that it may be that very early in the history of life on a planet there’s a bottleneck that occurs. Particularly a bottleneck that occurs in going from one cell organisms to multicell organisms. On our own planet one cell organisms appeared almost the moment earth was created, almost the moment it cooled down enough to support life. But multicelled creatures only occurred millions of years later and it may be that that jump, from one cell to multicell, it’s just too hard for to get through and we luckily got through it.

But Mario Livio said there’s also another bottleneck that occurs not at an early moment but a late moment. And this is by the way the reason that most people speculate we’re not finding life on other [planets]. And the explanation is that any group of creatures intelligent enough to have interstellar communication will also be smart enough to blow itself up and it will. And it will. And it has. That is that almost certainly other civilizations have existed and have not made it through the particular eye of the needle that we’re right now trying to get through.

So it’s for that reason that everybody on earth, all our resources on earth, all our ingenious scientists and humanists and theologians, etcetera, should be working together to get our planet through something that other planets haven’t gotten through rather than working at odds.

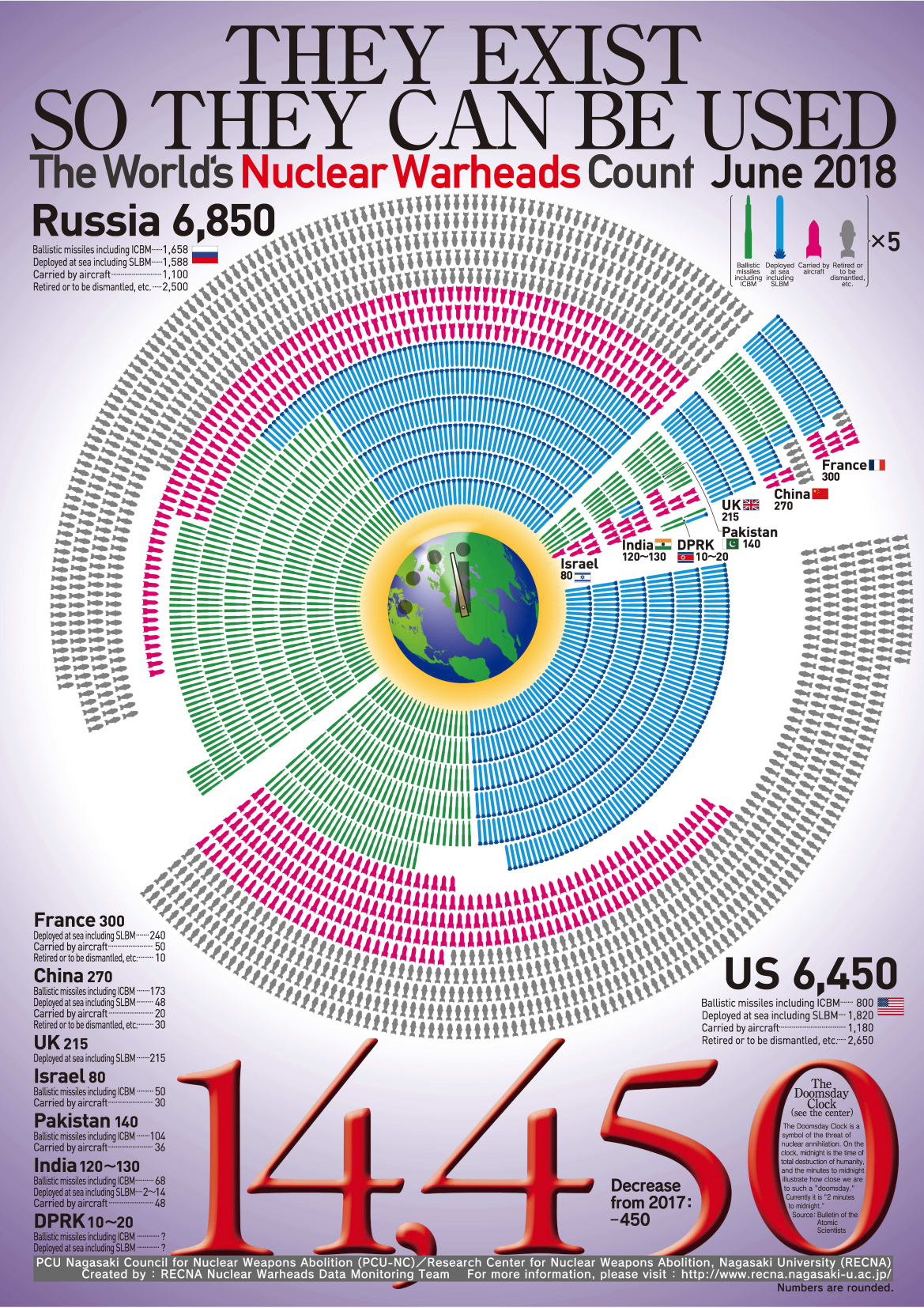

The World’s Nuclear Warheads Count June 2018

14,450

Now I don’t know what the weapon systems looked like on these other planets but this is what it looks like on our planet (and the screen isn’t perfect here) but just a couple of key things to say about it. Each of the little icons has to be multiplied by five. The total arsenal on earth is over 14,000 right now so if this were representing each of the warheads you’d have to take this and multiply it out by five and it would go way beyond any piece of paper that can hold it. But at least we can just multiply it in our minds mentally.

[Graphic source: Posters of World’s Nuclear Warheads produced by the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA), Nagasaki University. See Also: Guides to World’s Nuclear Warhead Counts. From the English Guide Introduction:

“The World’s Nuclear Warheads Count” is an easily understood illustration of the current state of the world we live in, showing more than 14,000 nuclear warheads in the world by country and by type.

The PCU Nagasaki Council for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (PCU-NC) and the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA) began producing this poster in 2013 as an educational resource for all audiences, from elementary school students to adults.

As part of the peace education efforts carried out every August at Hiroshima’s and Nagasaki’s Atomic Bomb Memorials, we present annual updates on the latest information every June.

The detailed data of this poster, which was compiled by the “RECNA Nuclear Warhead Data Monitoring Team,” including RECNA staff, has been published on our website. (http://www.recna.nagasaki-u.ac.jp/recna/nuclear1/nuclear_list_201806) Please see the website for further details. This data is updated from time to time.

We hope this guide will aid those using the poster in understanding background information and terminology in simple, plain terms. It should be especially useful in the education field, particularly in schools.

]

The key thing to know is that the United States and Russia together own 93% of all the missiles. Everything from about three o’clock around to about seven o’clock is owned by the United States and everything from there up to one o’clock is owned by Russia. And then that little wedge you see between one and two o’clock or the other seven nuclear states.

The other thing to know about that is that countries that we’re always hearing about are not on there. Iraq isn’t on there because Iraq doesn’t have nuclear weapons. Iran isn’t on there because Iran doesn’t have nuclear weapons. North Korea is on there but it’s the country with the smallest arsenal. The best estimates say it’s 20 or fewer missiles whereas the United States right now has over 6,000. Some people put North Korea’s estimate as high as 60 but the most reliable estimates still say that it’s 20 or fewer.

So it is a specific kind of architecture that is most to the credit or discredit of the United States and Russia who have one third of their arsenal’s on hair-trigger alert….

[Beginning at: 10:46]

We need language like “weapons of mass destruction” that registers the fact that there is this outrageous level of injury posed by these weapons. And yet we have to also look at the extraordinary and almost equally obscene fact that one person in our own country is ready to—stands ready to launch the weapons. That’s of course true of Trump, but it’s true of every president who’s been in the nuclear age.

If we were to go back two slides to the chart and if we took this whole thing as the weapon, that whole thing without a whole arsenal to be used, of course the Earth would be itself completely destroyed and all creatures on it. How many people would be responsible for the launch? There are nine nuclear states and it would be close to nine individuals. It might go as high as twenty or thirty in some cases. For example in the UK we know that the Prime Minister has a sealed envelope that tells the submarine captains if, in a nuclear exchange they can’t reach him, whether they should go ahead and obliterate Russia or not. So maybe we have to not just count the Prime Minister but the submarine captains.

But maybe thirty people. If you imagine that on another planet and you imagine there were billions of people on that planet, wouldn’t you think the billions of people on that planet could come up with something to get the thirty people to go into a room and say to them, You’re not coming out until you figure out how to dismantle these things. And something like that is what we probably need to do.

Elaine Scarry is the Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value at Harvard Univ. On 9 May 2019, she delivered the Nuclear Age Peace Foundations’s 18th Annual Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future in Santa Barbara, California. In addition to the NAPF transcript, the above excerpt includes additional sourcing.